> speaker notes

Introductions: What animal would you be & why?

Slides

#badhax

The Hacktory is concerned with the name of the GDI event that DMD is hosting. Her concern mostly revolves around the usage of the term Hacking. The Hacktory tries hard to make sure the term is used to connote an activity in which on object or piece of equipment is modified or otherwise altered for good, as opposed to implying any wrong doing. Is there an alternative title for the workshop that we could use instead?

Over the years I have to explain over and over the real roots of the word "hacking," which is a feat of technical skill… I also want to reclaim the word, but to do that when we use the word hack, it's either in a totally different context from software, or we are clear about not condoning or supporting illegal activities that some may call "hacking."

Kali Linux: Penetration Testing

The in-crowd calls it "pen-testing". If you like what you learn here today and you just want to turn it up to 11, this might be a good place to start your investigation. Install a hacking-optimized build of Linux!

Credo of the lock picker

Social Engineering

Most hacking is social engineering. Exploiting stuff like:

- most people write down their passwords and put them under their keyboard. Look under their keyboard while they're out of their cubicle.

- email gullible tech-ignorant people pretending to be their Gmail administrator, and tell them you need their username and password.

- call Amazon pretending to be a person you're attacking; use publicly available information about the person to convince the helpful service rep to give you slightly more info about them. Call Twitter support using this new information. Back & forth, through all their different services, until you get into their Twitter account. One account will give you the keys to all of their other ones.

There are a thousand examples like this. This is by far the most common and easy way of hacking.

But it's not particularly novel. It's just taking advantage of human kindness, not computer insecurities. Today we're going to talk about the more news-worthy, computer-security type of hacking.

Cookies

How websites remember you

A favorite activity of hackers is stealing cookies. Does anyone know why?

Cookies are how websites know who you are. Think about that.

Websites had no idea who you were, in 1993. They sent the same thing to every user who stopped by. There was no such thing as "signing in".

The web didn't change that much. But in 1994, the cookie mechanism was added.

Here's how it works: when you sign in to Gmail, Gmail says "ok, cool, here's a token that you can send me so that I know it's you." That is, it gives you a cookie. Then your browser remembers that cookie, and every time it grabs a page from Gmail, it sends it along. "I'd like this page, and here's that token you gave me." Gmail sees the token, does some work on its server to say, "oh, cool, it's you", and makes sure to give you your email, instead of someone else's. Without a cookie, Gmail would have no idea who's mail to show you.

You can actually inspect cookies in the Developer Tools in Chrome. Open up Chrome, open up a web page, and right-click somewhere and hit "Inspect Element" (or, to save time, hit cmd-shift-I). Go to the Network tab. Refresh the page. Now scroll to the top of the Network tab and click the first request. Here are some pictures to walk you through the relevant parts:

"Headers" are invisible-to-you bits of information that your browser and websites use to make sense of each other. "Request headers" are the headers that your browser sends to the website, when it requests a page from it. "Response headers" are the headers that the website sends back with its response.

Seven Layers of Networks

We need to start with something that seems pretty complex and overwhelming, but the tools that we're using later don't make sense unless you know this.

Remember, in order to pick a lock, you need to know how it works. We'll try not to go too deep—don't let your eyes gloss over! We'll just skim this stuff so that we know where to go to learn more.

You can do this. Ready?

Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model

The OSI model the process by which data moves from one computer to another out across the internet. Think of it, you can be checking email, working in google Docs, pushing to Github, and streaming music all at the same time. At some level, all of that information is just ones and zeros. It's just bits. Your ethernet cable and the fiber optic cable to your house are dumb, they're just sending ones and zeros. But somehow, your computer and your router are able to make sense of all of those bits, and make sure that Google Docs doesn't get the bits intended for Pandora (because that would look like garbage). But Google Docs itself doesn't have to manage all of that. Even Google Chrome doesn't have to manage the full range of that. There are separate layers, built into your operating system, that all work together to make this happen.

That's what the OSI model is.

[most of the following quotes about the OSI model are from http://null-byte.wonderhowto.com/how-to/spy-your-buddys-network-traffic-intro-wireshark-and-osi-model-0133807/]

The OSI model is a layered model that describes how information moves from an application running on one networked computer to an application running on another networked computer. Think of it this way, the OSI model describes the steps to be used to transfer data from one networked device to another. Easy.

Image: The OSI model: seven layers of networks

Ok! Big complicated image. And low quality! Sorry. If any designers are present, take note! The world would appreciate you making a better version of this.

The model is divided into seven layers, as shown [here]. If you are serious about learning networking and information security, my advice is to memorize this image. I know it looks long and complicated at first, and trust me it is. But the more you use this (and you will) the faster it will come to you.

The basic idea is this: each layer only talks to the layers above and below it. The Data Link layer (layer 2) only talks to the Physical layer (layer 1) and the Network layer (layer 3).

Other things to note in this picture: this is what packets are! This is where IP addresses and MAC addresses are used! If you're familiar with acronyms like TCP, UDP, or PPP, this photo can help you start piecing them all together in context. Each of these systems and protocols can be developed and tweaked separately from each other, but the end user and even the developers a couple layers away never have to know anything about it.

Note that people make entire careers dealing with specific tiny aspects of each layer. It's unlikely that any one person knows all there is to know. Think of it—most Girl Develop It classes, most of web development in general, deals only with Layer 7. Applications. All a web developer needs to know about, by and large, is Layer 7. Sometimes, when "résumés" shows up as "résumés", a web developer will need to dip down into Layer 6 (specifically, Character Code Translation), but that is low-level, unhappy stuff for a Layer 7 engineer (which you all are). Each layer only needs to know about the adjacent layers, and engineers on each layer barely have to know that much.

Question: What's a Layer 1 Engineer do? What company do they work for? (answer: run actual cable for Comcast. Or build actual cell towers for Verizon.)

The basic idea behind the OSI reference model is this—Each layer is in charge of some kind of processing and each layer only talks to the layers immediately below and above it. For example, the sixth layer will only talk to the seventh and fifth layers, and never directly with the first layer. Remember this and it gets easy.

Image: Each layer only talks to the layer above and below it

Perhaps this is a simplification of how all of this works, but here's the basic idea:

Let's say I click a Thumbs Up button on Youtube.

- At the application layer, we have Youtube.

- The application layer wants to send a message to Google's servers, saying to increase the number of likes for this video and to add this style of movie to my interests.

- To send this message to Google's servers, the application layer (Youtube) passes the data along to the Presentation layer

- The Presentation layer processes this data and deconstructs it a little bit. Let's say that the Youtube web app uses UTF8 and the Presentation layer translates all the characters into a binary encoding. Perhaps it also zips up the data, compressing it so it takes up less time traveling across the wire.

- The Presentation layer hands this zipped, encoded data to the Session layer. The session layer adds info about which app is sending this info—which logical port its on—to ensure that Pandora won't end up with the data that the Youtube servers send back.

- The Session layer hands this PDU (Protocol Data Unit, which is what the "stuff" that each layer deals with is called) down to the Transport layer, for which the data is called a Service Data Unit (SDU, which is what the "stuff" is called as it's handed on to a next-door layer). The transport layer encrypts this data and breaks it into separate pieces called Packets before passing it on to the Network layer.

- The Network layer adds its own, layer-specific info, such as the IP address of the YouTube servers, and passes on its PDU to the Data Link layer.

- The data link layer does its thing, adds the MAC address of the specific server over at Youtube that should receive this data, and passes its PDU on to the Physical layer.

- The Physical layer adds the last bit of wrapping that is needed to make my simple Thumbs Up click really ready to send over the wire, and then it actually sends it over the wire! Woo!

- Over on Youtube's servers, a similar process plays out in reverse. The Physical layer gets the raw bits, unwraps them a little, and hands the to the Data Link layer.

- The Data Link layer unwraps them, checks to make sure the MAC address is correct, and if so, passes the unwrapped SDU on to the Network layer.

- The network layer unwraps it a little more, checks the IP address, and passes the unwrapped data on to the Transport layer.

- The Transport layer reassembles data from the packets and then decrypts the data, turning them into a little bit closer to what the Youtube app developers (who are also Layer 7 engineers) deal with, and passes it on to the Session layer.

- The Session layer unwraps it a little bit more, makes sure that the request goes to the right place in the server, and passes it on to the Presentation layer.

- The Presentation layer unzips the data and translates the character encoding, and

- The Application layer knows just what to do with this pristine bit of data. It stores the correct information and sends a request back to me, the original clicker of the Thumbs Up button, to tell the page to make the button look like it's pressed in.

- And back the other way the data flows!

When your computer is transmitting data to the network, one given layer will receive data from the layer above, process what it received, add some control information to the data that this particular layer is in charge of, and send the new data with this new control information added to the layer below.

When your computer is receiving data, the contrary process will occur. One given layer will receive data from the layer below, process what it received, remove control information from the data that this particular layer is in charge of, and send the new data without the control information to the layer above.

Image: The seven layers pictured a third way, taken from Wikipedia

What's important to keep in mind is that each layer will add or remove control information that it is in charge of. An acronym to help remember the model from bottom to top is “Please Do Not Throw Sausage Pizza Away.”

Layer 1: Physical: The physical layer describes the physical medium that data travels through. Think Ethernet cables, Network Interface Controllers, and things of the like. It also provides the interface between network and network communication devices.

Layer 2: Datalink: The datalink layer is where the network packets are translated into raw bits (00110101) to be transmitted on the physical layer. This is also a layer that uses the most basic addressing scheme, Media Access Control addresses. Think of a MAC address like a diver's license number—it's just a number that is unique from anyone else's.

Summary of Layer 1 and 2: When a network card receives a stream of bits over the network, it receives the data from the wires (the first layer), then the second layer is responsible for making sense of these 1s and 0s. The second layer first checks the destination MAC address in the frame to make sure the data was intended for that computer. If the destination MAC address matches the MAC address of the network card, it carries on.

Layer 3: Network: The network layer determines how data transmits between network devices. It also translates the logical address into the physical address (computer name into MAC address). It's also responsible for defining the route, managing network problems, and addressing. Routers also work on the network layer.

The most important part of understanding this third layer is knowing that routers make decisions based on layer three's information. Routers are machines that decide how to send information from one logical network to another. Routers understand the Internet Protocol (IP) and base routing decisions on that information.

Layer 4: Transport: The transport layer accepts data from the session layer and breaks it into packets and delivers these packets to the network layer. It's the responsibility of the transport layer to guarantee successful arrival of data at the destination device. Transport Layer Security also runs on this layer.

Layer 5: Session: The session layer manages the setting up and taking down of the association between two communicating end points, called a connection. A connection is maintained while the two end points are communicating back and forth.

Another way to look at it—picture your computer. You're browsing the web, downloading from an FTP server, streaming some music, and who knows what else, all at the same time. All that data is coming into your computer, but it would make little sense if the FTP data was being sent to your Pandora tab, wouldn't it? It's in this layer that ports are used and that data is properly directed.

Layer 6: Presentation: The presentation layer resolves differences in data representation by translating from application to network format, and vice versa. It works to transform data into the form that the application layer can accept. Remember, each layer can only 'talk' to the layer above and below it.

This layer is mainly concerned with the syntax and semantics of the information transmitted. For outgoing messages, it converts data into a generic format for the transmission. For the incoming messages, it converts the data to a format understandable to the receiving application. This layer also formats and encrypts data to be sent across a network, providing freedom from compatibility problems and issues.

Layer 7: Application: The application layer is the top layer of the model. It provides a set of interfaces for applications to obtain access to networked services. This layer also provides application access security checking and information validation.

Common services that will seem familiar include streaming music, email, and online games. When you think of the application layer, think of just that—applications.

Upside-Down-Ternet

This is a link! But it's hard to click. Oops.

If you're bored of protecting your home network with a simple password, and you understand some of these network layers well, you can do something like this instead. If someone with an unrecognized device joins your network, you can flip all of the images they see upside down!

Ok, so Wireshark

Everyone open Wireshark. We're going to start snooping on each other.

Once everyone takes a look, we'll go through and analyze what we're looking at.

Here I've clicked on one network request on the top, and it's broken it down into the separate OSI layers on the bottom. Can anyone identify what this first layer is? Layer 1? Layer 2? Layer 7??

First person to hack me gets 5cɃ

Have actual 5cɃ gift cards printed out! (worth about $20 at the time this class was created)

At this point, open the Cat Meanings website, and start the sign_in_loop script in your terminal. Show the class your terminal, and explain that you are simulating sitting there & constantly signing in & out of the website, to make it easier to hack you.

Now, Cat Meanings isn't using HTTPS, which means the password is being sent over the network in plain text. If all goes well, students will be able to see your wireless traffic from their Wireshark interface, and peep at the form data, which will show them your username and password.

This actually did NOT go well during the first class! For some reason, we were not able to see each other's network traffic in Wireshark! FIGURE OUT HOW TO FIX THIS AHEAD OF TIME!!

Second person to hack me gets 5cɃ

This is a similar exercise, but instead of stealing the actual password, all they need to steal is your cookie, which signs them in as you!

Sign into Cat Meanings, and show them your cookie in your Edit This Cookie Chrome extension. Review how cookies work.

Then start running the browsing_loop script in your terminal, and explain that it's simulating you sitting there & browsing around the Cat Meanings website.

The most astonishing part of this is that it works even if the sign in page uses HTTPS. If the pages within the site are using non-secure HTTP (and a lot do!), then the cookies will be readable to anyone snooping on network traffic. And once I have your cookie, I can pretend to be you on that site, just by entering the cookie into Edit This Cookie.

Have them try to do it.

Firesheep

(baaaa)

Firesheep is/was a Firefox extension that was built to demonstrate how stupid it is for websites to have non-HTTPS browsing after a user makes it past the sign-in page. When you can get it to work, it shows a sidebar in Firefox with a list of usernames & profile pictures for different services—it grabs these from people on your network. It's basically doing all the work of the previous exercise for you—snooping on network traffic, looking at the cookies and where they were being sent.

Then it lets you click on a user and poof—be signed in as them! All it takes is a simple click and you can end up being signed into StackOverflow as someone else (SO, at the time this class was made, was still using plain HTTP after the user was signed in).

Is Firesheep evil? No. Firesheep was made to point out how careless app developers are when they don't use HTTPS everywhere, and how vulnerable it makes website users. Shortly after it came out, Facebook and many other sites started using HTTPS everywhere. Firesheep made internet users everywhere much safer, by making it very obvious just how much danger they were in.

XSS

Cross-Site Scripting

<input type="search" name="q" value="harper">

<input type="search" name="q" value="

"><script>alert(document.cookie)</script><input type="hidden

">

X-Xss-Protection: 0

Making it last

Caught with my hand in the Catnip Jar

XSRF/CSRF

Cross-Site Request Forgery

<form action="/users/dumb_update" method="get">

<img src="http://catmeanings.herokuapp.com/users/dumb_update?user[email]=lol%40lol.lol&user[password]=p0wned&user[password_confirmation]=p0wned" />

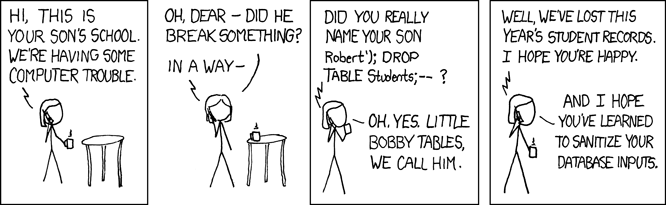

SQL Injection